For years I’ve been mildly obsessed with canto 30 of Dante’s Purgatorio—in particular, what happens to Virgil afterwards.

In the canto, Virgil has led Dante up mount purgatory to the edenic garden that lies just below paradise. He’s been Dante’s guide for the last sixty-four cantos, down through hell, where the damned are punished, and up through purgatory, where the saved are cleansed. But as a pagan, he can’t lead Dante through heaven. So he hands the pilgrim over to Beatrice, Dante’s onetime earthly beloved. Then he disappears. Dante turns around and he’s gone: “But Virgil had departed, leaving us bereft.” We never see him again.

Virgil returns, presumably, to where he came from: limbo, the circle of hell reserved for virtuous pagans. In limbo, the only punishment is longing. “Barred from hope, / we live on in desire,” Virgil explains. Born before Christ, these damned yearn for him forever. Most, Dante implies, don’t really know what they’re missing. How could they? They lived too early; they don’t have the language. I imagine their yearning like an unplaceable itch, a vague sense of offness. They can’t ever be happy about their achievements, though they’re all pretty famous—Homer, Ovid, Lucan. Some color, some richness, is lacking. They couldn’t name it if they tried.

Virgil, though. As he leads Dante up the mountain, it becomes clear that he knows his need, though he doesn’t know what it would mean to fill it. Until canto 30, when he stands in the garden of earthly paradise and looks up.

And suddenly there above him, opening its petals of light, is the thing he’s never known he’s always wanted. Heaven’s white rose, god’s city: the shape of the hunger he closed his eyes on every night in life. He’d always dismissed it as self-pity, the futile longing of limbo that he imagined everyone just dealt with; the desire he tried falteringly to describe to Dante without fully understanding it.

There it is. He can name it now. It was real all along.

*

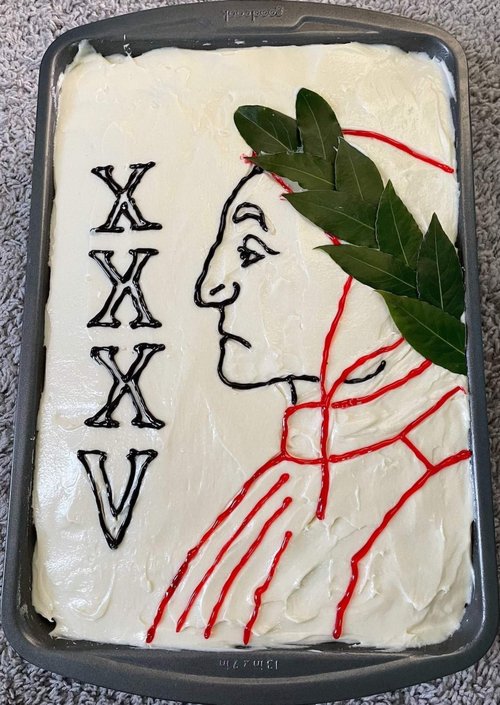

When I realized I was trans it was like being hit by a bus. It was early February 2020, and I was almost exactly halfway through my 35th year. Nel mezzo del cammin di nostra vita. That summer I was looking forward to having a Dante birthday party—a year late, since I’d been out of town in 2019. It was the only birthday party I’d ever really looked forward to, the only one I put thought into planning. I was more excited to turn 35 than I’d ever been to turn 21, or 30.

I was also deeply smug, though I couldn’t have articulated that to myself. Dante, the poor schmuck, hit 35 and got lost in a dark wood. I, on the other hand, had my shit figured out. I had tenure at a good school with good colleagues; I was married to a man I loved, living in a small city that was as good as the US can do, small-city-wise. I never felt happy about my career achievements, but I figured that was because I understood they were 60% privilege, 40% luck. Like all institutions of late capitalism, the academy can be hellish, but I’d stumbled into a liveable life there. I couldn’t, shouldn’t, be happy about it—just relieved, and a little deflated. And that was normal. Isn’t that what it meant to have your shit figured out?

Anyway. So I was halfway through 35 and halfway across a street on my walk to work. Some guys in nice peacoats were walking in front of me. As I watched them something in me burst. A surge of envy roared through my stomach, so strong it made me nauseous. I hated them, hated them, hated them—which is to say I recognized how much I hated myself. I made it across the street and to my office before I broke down.

If you’d asked me about my gender even a month before, I would have looked at you and shrugged. Even as I was sobbing in the basement of a Macy’s men’s section, distraught that I didn’t fit any of the clothes. Even as I was halfway through writing a novel about gay men, hating myself that I couldn’t stop. Even as every picture of a trans man I saw made me think, wow, he looks so happy.

I am very stupid sometimes.

*

When I say mildly obsessed with canto 30, what I mean is that I’ve spent a decade trying to write the story of what happens to Virgil next. At least six versions languish on my hard-drive. All end the same way. Virgil, after returning from purgatory, tries desperately to flee hell. Sometimes he goes alone, sometimes he takes Ovid and Hypatia, who’re amused by the idea.

He always fails. Always, he just crests the mountains that ring limbo before having to turn back. In the cruellest versions of the story, the journey nearly kills his companions. Virgil has to turn around not because he chooses to, but because the escape he wants so badly is hurting the people he loves. In the nicest versions of the story, Virgil doesn’t escape, but his return somehow changes limbo so that it’s more bearable—more colorful, warmer—and he can live there. In these versions Virgil isn’t happy, but he’s ok. He deals, forever.

I never sold any of these stories. Of course I didn’t. How could I? Who wants a story about failing to escape hell?

*

I’m telling this story mostly because I think it’s funny, and because I’ve heard we all get one self-indulgent coming-out post before retiring for five years to think about our sins. Trans-realization-wise, there’s nothing new here: lots of us come up with ways to distract ourselves from ourselves. Mine was just very allegorical.

In all the versions of that Virgil story I tried to write, I never once considered that Virgil could simply opt out. Stand up, look around at limbo’s grey fields and grey sky and wacky system of punishment and say, no thanks. You’d think the sometime-allegory of reason should be able to think his way out of something so obviously silly. But reason, as it turns out, is a welterweight compared to desire. This is the whole thesis of the Divine Comedy. It’s why, Dante implies, Virgil never does escape hell. He never figures out how to properly want out. Rather he wants—at some deep, self-punishing level—to stay.

Living as a woman was never hell for me, mostly for the same reasons that I landed a tenure-track job: luck and a lot of privilege. But I still couldn’t see outside it. I didn’t know wanting otherwise was possible. I got very, very good at finding other reasons for my desires. Like Virgil, my reasons were usually forms of self-damnation (I dress masc because I am too cowardly to take the shit femmes take; I write stories about gay men because I am a fetishist; I want a suit because I’m wasteful; I hate my body because I have an eating disorder).

I’m still not sure what changed, though I think it must have something to do with having a career with a purgatorial structure. The tenure-track is a series of terraces, moving targets for desire. Advancing up it, I always had something new to want, to flog myself for potentially not achieving: the PhD, the VAP, the book. Until tenure, the top of the mountain, when there was nowhere else to climb. I had to stop, squint down at my life, and confront questions about what I wanted out of it that I had studiously ignored since 22. And even then, it was not so much letting myself want as want standing up to sucker-punch me. Like Virgil, I could never have reasoned my way to it—perhaps because, like Virgil, I had hoped reason was enough. A desire I couldn’t explain, much less explain away? Impossible. Terrifying.

After, I had to come to terms with letting myself act on that desire. It was hard for some familiar transmasc reasons (but I hate and fear men! am I betraying feminism?, etc). Other people have written movingly about these anxieties. I won’t rehearse them, beyond noting that I think I’m a better feminist now, because I had to lay down my fear of losing an imagined moral high ground: the at-least-I’m-not-a-man security blanket of white ciswomanhood, which I had pretended to myself was a fear of losing solidarity with women. That solidarity was always fake, set up as it is to exclude BIPOC, trans women, disabled women, and others. The high ground was never real either. It was a lie I told myself about safety—not my own, but how safe I was for other people. I was not safe. I never will be. No one is.

I don’t know what lies about himself Virgil would have needed to relinquish to escape. I’m not even sure what escape would mean to him. Gaining paradise? Walking out of limbo? Simply refusing to see the place as damned—building a hell in heaven’s despite? The allegory breaks, thinking of it. Dante’s system isn’t watertight, but it is pretty totalizing.

Thankfully, gender isn’t. I no longer feel the need to finish Virgil’s story. The urge is completely gone; accepting transition fulfilled it. I find this very funny. What a basic-bitch relation between text and subtext! I’m as bad as Dante putting all his enemies in hell.

But I do sometimes like to imagine where Virgil might go, should he wake up one day and opt out. For the banal allegory I’ve drawn here to work—gender as Christianity, transition as paradise—he’d have to be saved and climb up purgatory, to god. But I’m not sure I like this reading. For one thing, I hate the idea of transition as an exclusive club, open only to those who’ve suffered for it. For another, Dante’s paradise is pretty boring.

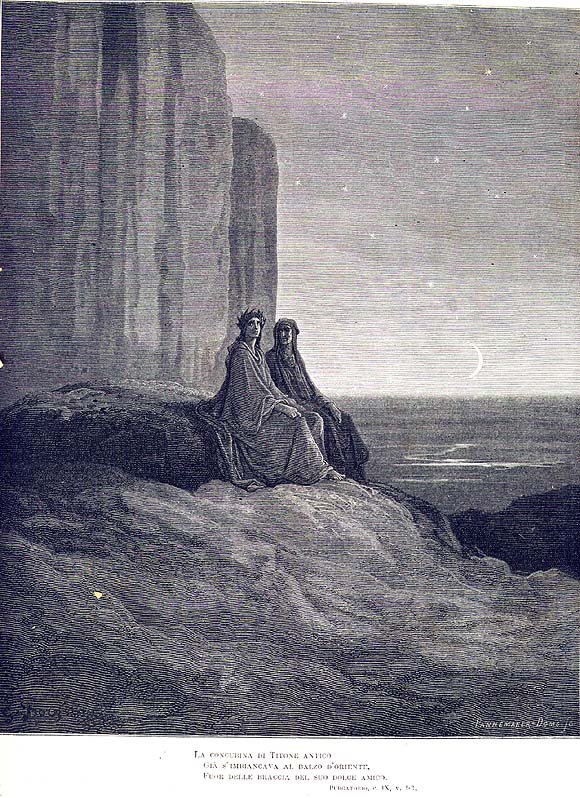

So instead, I’ll imagine Virgil in my other favorite part of Purgatorio. In cantos 1-2, Dante and Virgil, exhausted from climbing up Satan’s bum, rest at the base of mount purgatory. Dawn breaks white and rose. The sea laps through a marsh of low reeds. “We tarried on the seashore,” writes Dante.

The shore is a quiet breath between two worlds. It’s neither hell nor purgatory, but outside both, beyond them. The lit prof in me wants to say liminal, but it’s more peaceful than that. For one still moment, Dante and Virgil linger outside the system of reward and punishment. Of the many things transition has given me, peace is not the least.

So let’s say that after sending Dante to heaven, Virgil wanders back down mount purgatory. He reaches the shore. Over the sea, the sun is falling pink from a thin blue sky. Quiet waves ripple through a salt-marsh. Cato must be around here somewhere, he thinks. I should say hi. Then he thinks, I wonder if I could get Ovid and Hypatia up here. I bet they’d like it.

Further up the dunes, thickets of white briar rose shield the backs of nesting gulls—hundreds of roses, thousands, more than the petals of heaven, blooming softly in the sunset.

Virgil sits down on the cool sand. Close by, the hole to hell breathes ice. He stares at it, remembering limbo’s grey sky, grey mountains, grey plains sparsely populated by everyone. Well, I should go, he thinks.

Then he lies back, hands behind his head. The wind smells of salt and roses.

He doesn’t move.

*