I read less in 2022 than I did in 2021, partly because my brain was exhausted by novel edits, partly because in November I stepped into an admin role at work whose onboarding required more nights/weekends than I anticipated. Still, it was a good reading year: Sofia Samatar’s incredible memoir The White Mosque came out, there were several great trans books, and I read Patrick Leigh Fermor’s masterful travelogue The Time of Gifts for the first time. I also re-read several old favorites, whose length, if I were seeking excuses, I might name as the reason I read less in 2022: Hugo’s Les Misérables, Melville’s Moby Dick, and Dante’s Purgatorio.

As last year, the list below is in rough chronological order-of-reading. If I read several books by the same author, these appear together rather than in the order I read them, and I’ve decided to open with the writer I spent the most time with this year, Bryher (plus a small sidenote on transmasc historical fiction).

Let’s go!

*

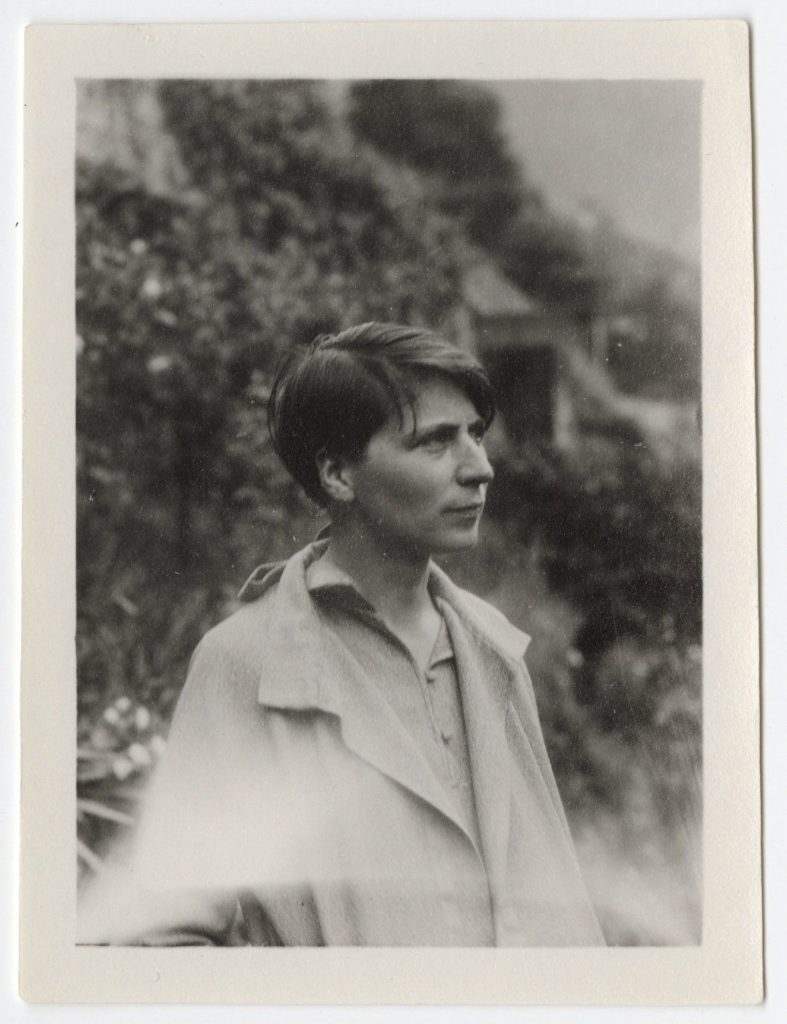

First, a note about the writer who I spent the most time with this year: Bryher.

Bryher is best known for being poet H.D.’s life-partner and financing, via an inherited shipping fortune, nearly every major Modernist except Pound, whom she hated. She was pretty clearly what we’d now call transmasculine, maintaining since childhood that she should’ve been born a boy. She spent the 1930s and 40s using her money to save people from Nazis. Of particular interest to me, she was a historical novelist who, like Mary Renault, was devoted to capturing an age’s zeitgeist—and did so through meticulously-researched versions of boy’s-own-stories.

(There is something vaguely transmasculine about this. Not just the obvious desire to inhabit a past of boyish adventure, but the obsession with historical accuracy. Trans writers love a historical novel, but on the whole the boys seem more worried about getting history “right”—or if they aren’t, are so seduced by historical fidelity they feel the need to mount theoretical arguments against its possibility. I’m not sure why this is, though I suspect it’s a hangover from faith in Enlightenment modes of proof, rerouted towards self-legitimation: if I get history right and people like me existed in history, it proves I exist. Embarrassingly, it probably helps that these modes are coded masculine. Oof, my guys. Because trans femmes are often refused these modes of proof, they chuck the Enlightenment’s shady logic in favor of playful experiments. Caveat to all of these generalizations: I’m talking about anglophone writers mostly from the US/UK; this impulse might look different or not exist elsewhere).

Anyway. In 2022 I read a lot of Bryher: four memoirs and six novels. While I didn’t read them all at once, I’ve clumped them together below. The rest of my 2022 reading follows.

Memoirs:

Bryher, Development (1920), Two Selves (1923).

Bryher’s early efforts to do a Modernism before she found her real métier (historical fiction). While blunt and awkward, these short memoirs are terrific documentary accounts of what we’d now call an early 20th-century trans childhood.

Bryher, The Heart to Artemis (1962).

A remarkable chronicle of the profound changes that overturned Europe in the early twentieth century, and a thoughtful reflection on history, art, gender, sexuality, and politics.

Bryher, The Days of Mars (1972).

An equally remarkable account of the Blitz, which Bryher endured with H.D. in a London flat, and a meditation on art, war, and national spirit.

Novels:

All of Bryher’s historical novels are set at minor end-times in history, when civilization is failing and the barbarians are at the gates. Roman Wall and Gate to the Sea end with physical flight, like Visa for Avalon (her one non-historical, set in an imaginary Europe beset by fascism); The Player’s Boy ends with a failed flight and murder, Ruan with a semi-suicidal sail West. It’s as if Bryher relived her own flight from the Nazis in 1942 again and again in different historical eras, playing out alternatives: being killed (The Player’s Boy), committing suicide like her friend Walter Benjamin (Ruan), or what actually happened—watching her world change irrevocably and facing those changes with the stubborn, head-on pragmatism she assigns to her boy heroes (Roman Wall, Gate to the Sea, Visa for Avalon).

Bryher, West (1925).

Only technically a novel, this brief, vibrant roman à clef tells how Bryher went to America because its poets made her love it, only to find the poets were writing to escape it. Contains a delightful portrait of Amy Lowell as a pterodactyl.

Bryher, The Player’s Boy (1953).

True-to-life evocation of Elizabethan England, which I would have liked better had I cared about Elizabethan England. Meditative, nostalgic, a book about watching the passing of time happen.

Bryher, Roman Wall (1954).

An account of the overthrow of the Roman outpost at Lausanne, and essentially a love-letter to the Swiss countryside.

Bryher, Gate to the Sea (1959).

Another love-letter, this one to Paestrum; contains that surprisingly rare character in Bryher, a girl-who-insists-she’s-a-boy.

Bryher, Ruan (1960).

Another meditative almost-bildung and a good showcase for the trademark quality of Bryher’s historical fiction: characters haunted by glimpses of the deep past amid a world tumbling toward an unclear future.

Bryher, Visa For Avalon (1965).

People compare this book to The Berlin Stories, but they’re nothing alike. Isherwood is wry and literal. This is a deeply psychological allegory about why we flee fascism and the havens we flee towards. Avalon is not some anonymized European neutral zone but Avalon: death, myth, nostalgia, the isle of apples (Bryher did so much psychoanalysis that her fiction drips with it).

*

Thomas Mann, Death in Venice and Seven Other Stories, trans H.T. Lowe-Porter (1912, 1989).*

Virginia Woolf, The Waves (1931).

Luminous character portraits that locate differences between people not in opinions but gestalts, the deep, inarticulable settings that govern what we notice about our surroundings.

Mary Renault, Return to Night (1947).

Another of Renault’s non-historicals that tries valiantly, and fails charmingly, to explore heterosexuality. So Freudian that it literally ends in a cave.

Émile Zola, Germinal (1894).

An unflinching account of a coalminers’ strike.

David Sweetman, Mary Renault: A Biography (1993).

H.D., Trilogy (1944-46).

Ecstatic and hopeful, even if its allusions are an impenetrable ouroboros.

Kaveh Akbar, Pilgrim Bell (2021).

Runs the lush romanticism of Calling a Wolf a Wolf through a sieve of reflection. The result is limpid and elegant, almost like Elizabeth Bishop.

W.H. Auden, The Age of Anxiety, Nones, The Shield of Achilles (1947, 51, 55; re-read).

Auden wrote some of his best poems in these collections.

Hope Mirrlees, Collected Poems (1920s for Paris; others later).

Isaac Fellman, Dead Collections (2022).

I can’t be objective about this book, because never have I read something for which I (a millennial trans man of fandom experience) was so directly the target audience. It perfectly captures the brand of trans self-hatred in which punishing yourself for moments of joy—say, writing fanfic—is the compensation that allows you to keep having them. Fellman mildly indulges, while representing, that self-hate: his lead gets beat up and claims to deserve it; he even seems to like it, because it’s frightening for him to imagine desire without punishment. Big mood.

James Gurney, Dinotopia series (1995, 99, 2007; re-read).

Dinosaurs!

Marina & Sergey Dyachenko, Vita Nostra (2007).

Elizabeth Knox, The Absolute Book (2019).

Thornton Wilder, The Skin of Our Teeth (1942).

Branden Jacobs-Jenkins, Appropriate (2013).

An acid send-up of dysfunctional American whiteness, set on a slave plantation whose history every member of the family that owns it keeps trying to deny.

Dante, Purgatorio (1300 exactly, according to Dante; re-read).

My favorite book in the Commedia, because of Casella and Virgil. Oh god, Virgil.

Toni Morrison, Beloved (1987; re-read).

As visceral now as when I first read it. Morrison pulls off metaphors that lesser writers would spoil (literally, like fermenting), which should be purple but aren’t.

Aditi Machado, Emporium (2020).

Anne Carson x John Ashbery, an exploration of the fine line between others and self, language and idea, interior and exterior (its thesis comes in the second poem, “Social Gesture”: “I struggle to see / how each body is separate, no precision / that isn’t imprecision.”)

Moniza Alvi, Europa (2008).

Spare, with an occasional extraordinary image rising up through it like an island on the horizon.

Nicola Griffith, Spear (2022).

An evocative little fable that flies clean and true as an arrow, and which it is unfair of me to fault for not being Menewood (next October!).

Sally Rooney, Normal People (2018).

Unflashy, accomplished character work.

Daphne du Maurier, Rebecca (1938).

An indulgent gothic headtrip whose narrative deceptions are so bald it’s amazing du Maurier pulls them off.

Louise Gluck, The Wild Iris (1992).

J. L. Carr, A Month in the Country (1980).

Such an intimate portrait of WWI trauma and nostalgia for antebellum England it’s astonishing it was published in 1980.

Aysegül Savas, White on White (2021).

William Maxwell, The Folded Leaf (1945; reread).

Louisa May Alcott, Little Women (1868-9).

Casey Plett, Little Fish (2018).

I spent most of this novel wishing its exhausted lead could catch a good night’s sleep.

Katherine Addison, The Grief of Stones (2022).

Like fanfiction of Addison’s earlier book, and satisfying in the way fanfiction is.

Bishakh Som, Apsara Engine (2020).

A collection of eerie shorts whose gorgeous illustrations and understanding of desire’s treachery give its weirdness a sharp resonance.

Julia Serano, Whipping Girl (2016 revised edition).

No wonder it’s a classic: this is still the clearest trans 101 I’ve ever read. Serano refuses to dumb down the complexity of trans experience or file off its provocative edges.

Honoré De Balzac, Le Pere Goriot (1835).

Psychologically blunt platitudes (Nabokov was right: fake realism!); melodramatic without melodrama’s redeeming purple fun.

Francesca Momplaisir, The Garden of Broken Things (2022).

Mohamed Leftah, Captain Ni’mat’s Last Battle (2022).

Jeanne Thornton, Summer Fun (2021).

A hallucinogenic novel that ends in apocalypse, in the old revelatory sense; also a lush metaphorical high-wire act that delights in its own excess and bristles at all restrictions, formal or thematic. Much like its definitely-not-Brian-Wilson lead, it’s at once defiantly dismissive of confidence, men, and purity narratives—and drowning in self-doubt.

Kali Fajardo-Anstine, Woman of Light (2022).

A beautifully-crafted, elegantly plainspoken historical that never lets its research overwhelm its story.

Seyward Goodhand, Even That Wildest Hope (2019).

Weird fiction that strides confidently through the darkness, never weird for weirdness’s sake; assured prose about the deepest and most marvelous human impulses. The best collection I read this year.

Pat Barker, Regeneration (1991), The Eye in the Door (1993).

Barker’s WWI anti-war novels are what historical fiction should be, where the history is integral to the story but not its point.

Sarah Caudwell, The Sirens Sang of Murder (1990).

Another goddamn delightful Caudwell mystery, even funnier for being narrated almost entirely by Caudwell’s hapless Bertie Wooster homage, Michael Cantrip.

Thomas Halliday, Otherlands (2022).

Exactly what I want in my prehistoric nonfiction: well-painted landscapes and creatures beyond the Jurassic and Cretaceous dinolands (though I love those too).

John Steinbeck, Of Mice and Men, Cannery Row (1937, 45).

Susan McCabe, H.D. & Bryher: An Untold Love Story of Modernism (2021).

Fascinating material, intriguingly-written; McCabe seems trying to echo the brisk, stripped-of-grammatical-articles prose of her subjects’ writing from the ‘20s.

James M. McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (1988).

This magisterial history pulls no punches in documenting just how much huge swathes of white America really loved slavery.

Céline Huyghebaert, Remnants (2022).

An autofiction about Huyghebaert’s dead father, compiled from fictionalized(ish) interviews with her friends and family. Documentary novels sometimes feel like they substitute form for depth, but Huyghebaert builds her fragments into a rich, complex portrait of a difficult man whose love she desperately hoped to justify.

Victor Hugo, Les Misérables (1861; re-read).

Still my potted answer to the question “what’s your favorite novel?” This year was my sixth time through, and my first re-read since coming out. My understanding of it changed profoundly. I had thought Les Mis was a glorification of idealistic self-sacrifice (one of my favorite addictions, which I share with Hugo); turns out it’s also a critique of how this impulse is twisted by the prison system into a self-hatred indistinguishable from martyrdom.

Cat Fitzpatrick, The Call-Out (2022).

A sonnet novel, sharp and funny and a little helpless, like all my favorite poets. Also another entry in the series “how trans people train each other to be awful to each other,” whose affect brilliantly replicates the anxiety of scrolling trans drama on twitter. I heard Fitzpatrick say in an interview she was trying to offer “no opinions, only stories,” which is an oddly defensive defense of a book that’s refreshingly not defensive. I hope she writes a sequel (or three), and that they all rhyme too.

Kate Beaton, Ducks (2022).

Heartbreaking and humane graphic memoir of Beaton’s time in the tar sands.

Alex Myers, Revolutionary (2014).

Solid, historically-accurate novel (yes) about Deborah Sampson, a woman who enlists as a man in the US Continental army.

Herman Melville, Moby-Dick (1851; re-read).

Still slaps.

Sofia Samatar, The White Mosque (2022).

Samatar’s masterpiece. The memoir recounts her trip to Uzbekistan on the trail of her Mennonite ancestors. It’s arranged like a palimpsest of stained-glass shards, vivid moments held up to the light of her fierce, generous interest in people and the faiths that drive them. The resulting kaleidoscope layers lambent evocations of place over histories, personal and religious, that are narrow but resounding as wells. Throughout she’s enchanted (almost literally, like a spell) by loves so deep people suffer for them, while also being suspicious of suffering’s romanticization. The best new book I read this year.

Patrick Leigh Fermor, A Time of Gifts (1977).

I read Fermor directly after Samatar and he seems like her direct ancestor: erudite, generous, interested in everything. The book chronicles the first leg of his 1933 walking tour of Europe. I looked up more words reading this book than all other books this year combined, most terms for fiddly bits of churches.

*

That’s it! See you all again in 2023, when my own novel (historical and as accurate as I could make it [yes]), appears. In the meantime I’ll try not to be too insufferable about it.