I’ve given up posting regular reading dumps, but I’m committed to continuing the yearly overview. This year I read less than last by a few books, partially because I lost most of December to illness/vacation, partially because I taught an extra class in fall, partially because this year has been more dramatic—in good and bad ways—than 2020 for me. More on that in a later post, probably.

As last year, the list below is in rough chronological order-of-reading (though if I read several books by the same author, these appear together rather than in the order I read them). Starred entries are books I think are worth picking up (ie, most of them). Double-starred entries are books I adored. I’ve also included a mini-ranking of 8 Mary Renault novels. I hope to read more of her work in the coming year.

Let’s ride!

*

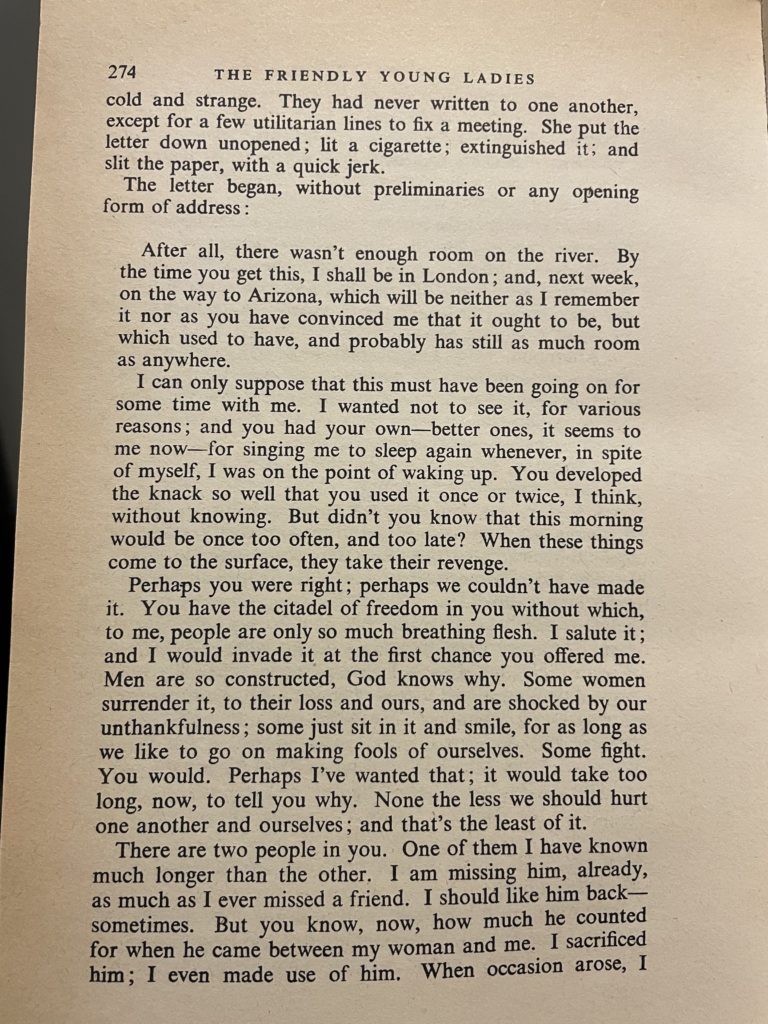

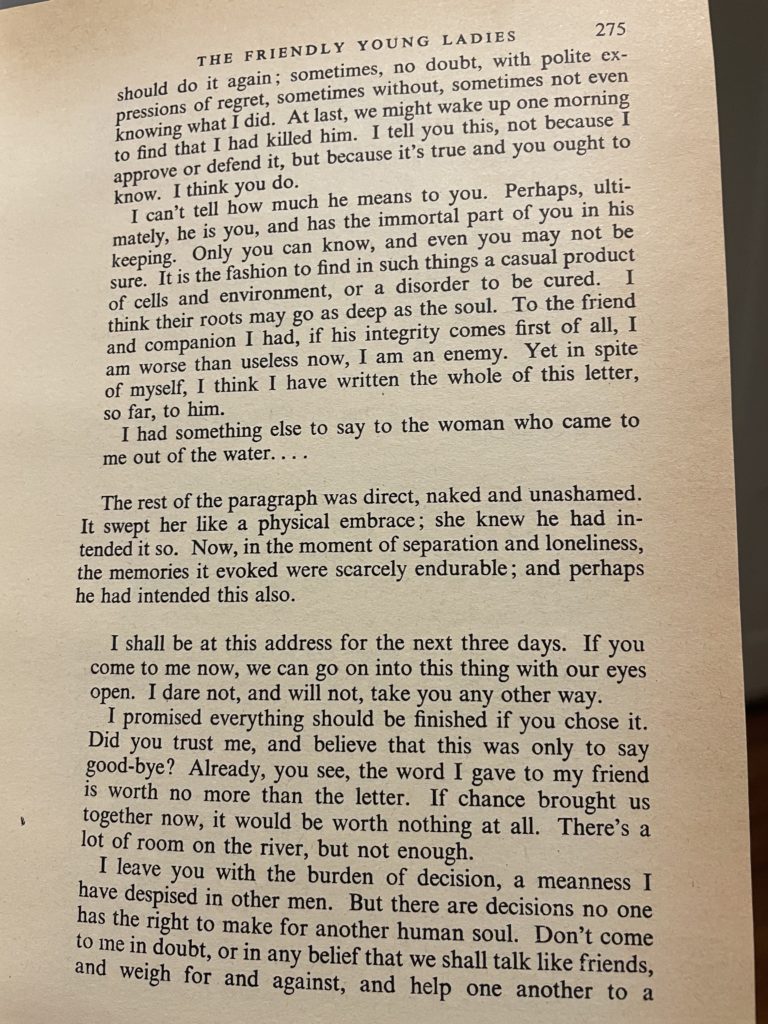

Image: from Mary Renault’s The Friendly Young Ladies (English title: The Middle Mist).

***

Patricia Lockwood, Priestdaddy (2018)**

A memoir that wrings humor and glimpses of transcendence from Lockwood’s relationship with her horrific (and thankfully-not-online) father.

Patricia Lockwood, No One is Talking About This (2021)**

Calvin Kasulke, several people are typing (2021)*

Mimetically, both of these internet novels are successful. Lockwood’s twitter book made me as anxious as scrolling twitter; Kalsuke’s slack book frustrated me as much as checking slack. But what I wanted from both and didn’t get—some kind of conclusion about what it means that certain people live so much of our lives online—was probably an unfair ask. Social media is still too new for anyone to take a long view of it. At least Lockwood comes by her moral (log off!) honestly. Forced offline by a family crisis, her lead rediscovers the tactile joy of IRL. Kasulke’s book thinks it’s too smart for this moral. We know this because he offers a few lengthy speeches troubling it, some of which echo ‘90s internet utopianism. But his book ultimately endorses log off too. It simply doesn’t know where else to go—though to be fair, that’s because the slack in question is a work slack and a metaphor for late capitalism, from which it’s also impossible to unplug.

Torrey Peters, Detransition, Baby (2021)**

As smart and funny as everyone says it is; a novel that refuses to either special plead for its trans characters or pity them, and isn’t afraid to laugh at them when they deserve it. Thank god.

Yanyi, The Year of Blue Water (2018)*

Brandon Taylor, Real Life (2020)**

A quiet, interior novel about navigating STEM grad school (specifically, UW-Madison) as a black gay man from the south; also a novel that bristles at being About any of those things, specifically.

Brandon Taylor, Filthy Animals (2021)*

A short story collection that’s secretly mostly a novella and would have been better had it come clean and admitted it.

Mikhail Bulgakov, The Master and Margarita (1967ish)*

A hoarse scream of a novel about what art can and can’t save.

James Downs, Anton Walbrook: A Life of Masks and Mirrors (2020)*

Anton Walbrook will always look better than us and I guess we all have to live with that.

Robert Jones, The Prophets (2021)

Rebecca Makkai, The Great Believers (2018)**

A lyrical account of the AIDS crisis from someone who didn’t live through it and is acutely interested in what it means to access a history that isn’t ours.

Nghi Vo, The Empress of Salt and Fortune (2020)

Stefan Zweig, The World of Yesterday (1941)**

Less nostalgic than you’d expect; a gentle evocation and indictment of the Vienna that would eventually capitulate to Nazi rule.

Jordy Rosenberg, Confessions of the Fox (2018)*

I’m the wrong audience for this book, as I share Rosenberg’s historical field and this read to me like a bingo card of “c18thist writes a transmasc novel.” By page 10 I was thinking, lol what if there’s a Burney top surgery scene—so when it happened I snorted. And I kept snorting. My more serious problem with the book is also somewhat professional. I’m a romanticist and believe in the self, however interdependent and slippery and fractured it might be. The lead character here is less a self than a palimpsest of (very sharp, very well-presented, admirably intersectional) arguments about gender and society. I never knew who he was, beyond a guy who really wants to be a good guy, which means loving women and hating capitalism. Those are theses I can get behind, and Rosenberg argues them well! But they don’t add up to a person.

Colum McCann, Apeirogon (2020)*

One of the better stabs at the novel-in-fragments I’ve read, though I still feel that this book and others like it (see: Offill’s Dept. of Speculation) believe their blank spaces are doing more heavy lifting than they actually are.

Karin Tidbeck, The Memory Theater (2021)

Douglas Stuart, Shuggie Bain (2020)*

So grim it got sucked into the Discourse about how grim queers are allowed to be when talking about their life experiences.

Adam Mickiewicz, trans. Bill Johnston, Pan Tadeusz: The Last Foray in Lithuania (1834)**

A light-footed epic with a lot of delightful set-pieces, which makes its occasional, successful dips into brooding pastoral all the more remarkable.

Anna Burns, Milkman (2018)*

As grim as Shuggie Bain, but with more dialect and longer sentences.

Jackson Bird, Sorted (2019)

Charlie Jane Anders, The City in the Middle of the Night (2019)*

A quiet sociological sf about the lingering effects of interplanetary colonialism with a cast of vivid characters.

Özgür Mumcu, The Peace Machine (2016)

Ursula K. Le Guin, The Lathe of Heaven (1971)**

A thoughtful take on the “prophetic dreaming” trope, only slightly deflated by Le Guin’s insistence on passivity as virtue.

Jan Morris, Last Letters from Hav (1985)**

One of the best books I read this year, a travelogue about a fake country called Hav located somewhere just below Turkey—but also a miniature affective history of 20th century Europe. Morris creates Zweig-level nostalgia for a place that never existed, whose details are richer than many real accounts of real places. This book is what every Wes Anderson movie wants to be. I hope he never reads it so we never have to see him mangle it.

Tamsyn Muir, Gideon the Ninth (2019)*

Tamsyn Muir, Harrow the Ninth (2020)*

These books are what it says on the tin: lesbian necromancers in space! They’re swell gothy fun, though another example of a wider problem I’ve seen in sff lately, in that they mistake depicting an issue (here, trauma) for giving a meaningful account of it.

Katherine Addison, Witness for the Dead (2021)**

Like its predecessor The Goblin Emperor, this book unapologetically invites us to root for a good man trying quietly to do the right thing.

Lucie Elven, The Weak Spot (2021)*

A vague fable about why terrible people are compelling that refuses, Henry James style, to venture a concrete reason for any of its passive characters’ choices.

This year I read as many Mary Renault novels as I could physically get my hands on: 6 in total, which would have been 7 had I not lost my kindle on a plane in December. I’ve ranked them here alongside her novels I read last year (The Mask of Apollo and The Praise Singer). The ranking is wholly idiosyncratic and should not be taken as a guide to which novels are her best; consensus says that’s her Alexander trilogy, and consensus is probably right.

- The Charioteer (1953)**. My personal catnip: a cast of self-flagellating characters spend 300 pages agonizing about whether their desires (platonic and not-so) are, Platonically, Good. I loved this book so much I carried it around in my backpack for a month like a talisman.

- The Last of the Wine (1956)**. This novel is basically The Charioteer, only everyone’s happier and sacrifices themselves for the Good with a clear heart.

- The Friendly Young Ladies (1944)**. I thought this was going to be a lighthearted “lesbians on a houseboat” romcom. The lesbians are indeed on a houseboat, but at the end of the book the masc one, who has spent the novel happily seeing herself as a guy, falls in love with a man. Said man goes on to write a letter addressed to the “man” part of her, which he calls the “real” part, apologizing for killing him by loving her (no, I’m not exaggerating: see the image for this post). And this from a writer who thought Radclyffe Hall was melodramatic.

- The Mask of Apollo (1966)**. A thoughtful meditation on theater and the danger of idealizing individual saviors.

- The Praise Singer (1978).** A thoughtful meditation on poetry and artistic mentorship.

- Fire From Heaven (1969)**. Hephaiston loves Alexander the Great.

- The Persian Boy (1978)**. Bagoas loves Alexander the Great.

- Funeral Games (1981)**. Everyone loved Alexander the Great and now he’s dead and everything is terrible. This is the probably the best novel of the trilogy, because Renault’s characters have lost their polestar and now must navigate life via their own moral agency. By killing off her hero, Renault lets herself return to what she does best: examining how people with exacting principles bruise themselves on a world that can never live up to them.

Aja Gabel, The Ensemble (2018)**

Another of the best books I read this year, a carefully-evoked portrait of a friendship between four musicians spanning several decades. Gabel writes about art and aging with great warmth and grace.

Tayeb Salih, Season of Migration to the North (1966)**

A brilliant, difficult exploration of the psychological effects of colonialism.

Virgil, Georgics**

An impassioned plea against civil war disguised as a mild pastoral.

Plato, Phaedrus, Ion, Crito, Gorgias**

I listened to all of these in audiobook, where they worked surprisingly well (almost as if they were, you know, dialogues). Gorgias convinces me that the ironic reading of The Republic is the correct one; Plato deliberately allows Socrates to lose while not realizing he’s losing because he can’t abandon his principles long enough to recognize they’re not shared.

Sarah Caudwell, The Sibyl in Her Grave (2000)**

If P.G. Wodehouse wrote mysteries they would sound like this, silly and charming and meticulously-plotted. It’s a shame Caudwell only wrote four of them.

Penelope Fitzgerald, At Freddie’s (1982)**

I’ll just say what I said last year: everything Fitzgerald writes is worth reading, and she can do in two sentences what would take another writer two pages. And she’s funnier at it, too.

I read three novels by Alan Hollinghurst this year and plan to read more. His sentences are so good they’re almost transparent–not in a stripped-down modernist way, but as if he’d hit on the only proper way to describe something, which matches reality so precisely your eyes simply pass through it. Like Penelope Fitzgerald, if Hollinghurst had a book about dryer lint I’d read it, so it’s an added bonus he writes almost exclusively about gays acquiring art (in the list below, poetry, painting, and music respectively).

- Alan Hollinghurst, The Stranger’s Child (2011)**

- Alan Hollinghurst, The Line of Beauty (2004)**

- Alan Hollinghurst, The Sparsholt Affair (2017)**

William Maxwell, Time Will Darken It (1948)*

Marilyn Hacker, Winter Numbers (1994)**

Hacker remains an impeccable formalist and one of my favorite poets.

Tsitsi Dangarembga, Nervous Conditions (1988)*

Megan O’Rourke, Halflife (2007)*

Miriam Toews, All My Puny Sorrows (2014)**

Toews renders horrific tragedy graceful by staring it in the face and telling it honest, gentle jokes.

Robert Walser, The Tanners (1907)*

Homer, Iliad**

On this reread I found myself agreeing with Simone Weil: this is a poem about force and how exerting it maintains power. I was especially chilled by how the gods tiptoe around Zeus like abused spouses, terrified he’ll kill them if they piss him off.

Zoe Playdon, The Hidden Case of Ewan Forbes (2021)*

A decent pop-history of a key legal case in trans history, enlivened by the British quirk of needing to document every time someone might have met a Royal. I was disappointed that Playdon drew a hard line between “scientific medicine” and “pseudoscience” to dismiss transphobic medical care. “Scientific” medicine has a long history of shittiness, and a historian of medicine should know better.

Galsan Tschinag, The Blue Sky (1994)*

Edith Wharton, The House of Mirth (1905)*

P. G. Wodehouse, The Code of the Woosters (1938)**

Wodehouse is perfect for audiobook, though the reader of this one disappointingly pronounced “Fotheringay” as “father-ing-gay” rather than “fungi.”

Caroline Zilboorg, The Masks of Mary Renault (2001)*

A decent biography with some amusing Freudian readings. Despite her several protests otherwise, Zilboorg manages to conflate gender and sexuality—not by acknowledging that identity is a confusing bag of mixed fluids in which nothing’s really separate (which: true), but by treating sex/gender syllogistically: if X, then Y.

***

That’s it! I’ll be back in 2023, hopefully.