I had originally planned this post as a little discussion of an allusion I recently discovered in Ursula K. Le Guin’s Earthsea novel The Farthest Shore to Rilke’s tenth Duino Elegy. But as I re-read the novel’s penultimate chapter where the allusion begins, I realized the post was going to have to be much longer. Because in addition to Rilke, there was Dante. There is, I am learning, always Dante.

By the way, after finishing this post, I actually thought of googling the allusions I was discussing and came across this statement from Le Guin:

“The dark, dry, changeless world after death of Earthsea comes (in so far as I am conscious of its sources) from the Greco-Roman idea of Hades’ realm, from certain images in Dante, and from one of Rilke’s Elegies. A realm of shadow, dust, where nothing changes and “lovers pass each other in silence” – it seems a fairly common way of thinking about what personal existence after death would be, not a specifically modern one?”

It’s good to know that my instincts were right, though I can’t claim that the interpretation of these allusions you find below is the one Le Guin intended.

*

I won’t rehearse the whole plot of The Farthest Shore, but the final chapters explain how a power-hungry wizard called Cob cast a spell to cheat death, called the “Dry Land” by Le Guin’s characters. Her heroes, the wizard Ged and his companion Arren, have descended into the Dry Land to stop him.

The Dry Land is a dim, cold wasteland whose dusty walls slope forever downward. It is populated by everyone who has ever died, moving listlessly about in the dust. At the very bottom of the Dry Land rise the Mountains of Pain; the only way out for the living is through these mountains. After the book’s finale—Ged defeats Cob—Arren carries his tired master back up through the Mountains. Later, he finds a bit of rock from the Mountains in his shoe: “the unchanging thing, the stone of pain.” (The Mountains and their stone, by the way, are the Rilke allusions, and I will eventually return to them).

The Dry Land’s features are Dante by way of T. S. Eliot, who made Dante’s escape from hell by following “the sound of a narrow stream that trickles / through a channel it has cut into a rock” into a metaphor for his age’s profound disillusionment. In Eliot’s Wasteland, the water of life has run dry: there is no water, not even the sound of water, and therefore no escape from hell (unless the thunder speaks). Le Guin’s Dry Land is likewise dry—“Here they drink dust,” Ged tells Arren—and as seemingly inescapable:

Was there a way out? He thought how they had come down the hill, always descending, no matter how they turned; and still in the dark city the streets went downward, so that to return to the wall of stones they need only climb, and at the hill’s top they would find it. But they did not turn. Side by side, they went on. Did he follow Ged? Or did he lead him?

I do not think I am overreading to see in this image of two companions descending ever downward into hell, never turning, one mostly leading but not always, shades of Virgil and Dante. Arren’s desire to turn and ascend back up the hill from which they have come is as futile as Dante’s in Canto I: “It is another path you must follow,” Virgil tells him. You must go down to go up. And Ged and Arren do, reaching the very bottom of the Dry Land, the bed of the Dry River, before finally climbing up and out over the Mountains of Pain. They do not turn around once, as Virgil and Dante do not turn when ascending out of hell—instead, the world flips around them. (And in a beautiful inversion of the Inferno’s conclusion, where Virgil carries Dante out of hell, Le Guin has Arren carry Ged out of the Dry Land).

The heavily allegorical conclusion of The Farthest Shore also owes much to Dante. The book culminates in Ged and Cob’s confrontation at the Dry Land’s Dry River. Here, Cob has torn a hole between life and death into which life, like the river-water, has sunk away. “I opened the door between the worlds and I cannot shut it,” he says. “It draws, it draws me. I must come back to it. I must go through it and come back here, into the dust and cold and silence… I cannot close it. It will suck all the light out of the world in the end. All the rivers will be like the Dry River.” Cob’s very understandable, very human desire to cheat death endangers the integrity of the living world. To cheat death, Cob has sacrificed life, and punctured the world of the living—the world of water, Earthsea—so that it will drain away and become a Dry Land, too.

Le Guin is careful to spell out what this means. In exchange for immortality, Cob has given up the authentic experience of his own life, whose symbol, in Earthsea, is the “true name.”* “Where is your name? Where is the truth of you? … You have forgotten much, O Lord of the Two Lands,” Ged tells Cob. “You have forgotten light, and love, and your own name.” Cob’s shell—his body, personality, and “use-name” (Cob, spider’s web and seedless husk)—is mummified by emptying out its contents: life. He is like Dante’s sinners, who can see the past and the future but who are blind to the present, and who therefore lack all self-awareness. Cob too is blind, literally and figuratively. He has scooped his eyes out, and while Arren notes that “some wizardly second-sight he might have, such as that hearing and seeing that sendings and presentments had,” he lacks the only meaningful “true sight”—an understanding of himself. Cob’s literal danger to the world of Earthsea is that like Dante’s Satan, he is a crafty rhetorician who has already convinced many others to make his same disastrous bargain.

As I mentioned earlier, the book ends with Ged defeating Cob. After closing the rift between the Two Lands, Ged gives his enemy the gift of true death. On the surface, this seems like an acceptable conclusion: Ged keeps life and death separate, as they were meant to be. But this ending is only consolatory if we forget everything else Le Guin has told us about her underworld. Cob is, unfortunately, not the only Dantean tragedy in the Dry Land. He is not even the most tragic. Of the Dry Land’s people, Le Guin writes:

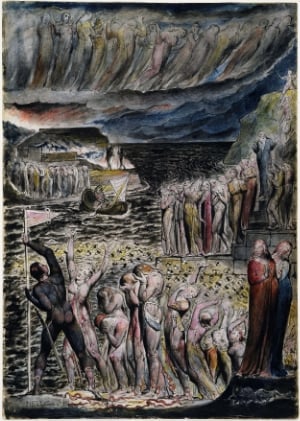

They [the dead] were not loathsome as Arren had feared they would be… Quiet were their faces, freed from anger and desire, and there was in their shadowed eyes no hope. Instead of fear, then great pity rose up in Arren, and if fear underlay it, it was not for himself, but for all people. For he saw the mother and child who had died together, and they were in the dark land together; but the child did not run, nor did it cry, and the mother did not hold it or ever look at it. And those who had died for love passed each other in the streets.

These “proper” dead seem almost worse off than Cob. While they might still bear their true names, they exist without hope, and also—more terribly—without desire (Cob at least has emotions, but a child cannot even want its mother in the Dry Land!). There is only one class of damned in Dante’s Inferno that exhibits these qualities, but after Eliot’s “Hollow Men,” they have become representative of what Eliot thought the trademark sin of modernity. They are the indecisive, souls who occupy the antechamber outside of hell proper. Of them, Dante writes:

This miserable state is borne / by the wretched souls of those who lived / without disgrace yet without praise… Loth to impair its beauty, Heaven casts them out, / and depth of Hell does not receive them / lest on their account the evil angels gloat… They have no hope of death, / and their blind life is so abject / that they are envious of every other lot. / The world does not permit report of them. / Mercy and justice hold them in contempt. / Let us not speak of them—look and pass by.

Every sinner in Dante’s hell lives without hope, even those in Limbo; however, only the undecided exist without desire, since every other sinner in hell is there because they directed their desire to something that wasn’t Dante’s god (sex, money, themselves). The undecided are objects of contempt to the other damned because they could not even muster enough desire to ignore god properly. Le Guin takes their condemnation a step further by positing that the worst hell is not misdirected desire but its total absence. The souls of the Dry Land are not damned, but this is because they are no longer human: they cannot desire, so they cannot love, aspire, hope. They are mere outlines of humanity, literally shades, whose every inessential detail—body, clothing, and name—has been preserved at the expense of the essential. Hollow men, as Eliot would have it (and whose revision of Dante’s antechamber Le Guin is surely nodding at). Arren, like Dante, can only pity them.

But what is truly chilling about Le Guin’s dead is that their state already entails the sort of damnation Cob brings on himself, the destructive fraud Le Guin offers as Cob’s threat to the living world. Cob has sold his life to become an immortal shell, but this is what the people of the Dry Land already are—eternal and individual, yet utterly empty, neither truly living nor truly dead (When Ged asks Cob where he is, he says, “Between the worlds.” “But that is neither life nor death,” Ged replies). Here is the paradox lurking beneath The Farthest Shore that Le Guin would attempt to resolve with Tehanu and the later Earthsea books. By preserving the separation of life and death, Ged condemns the dead to be shucked people: cobs. So while Le Guin’s Dry Land has debts to Eliot and Dante, its vision is ultimately Homer’s, a grey Elysium where the shade of Achilles reveals the real tragedy of death to Odysseus, his inverse: death is the embalming of life. Death transforms a full-blooded self into a shadow, an individual who can know herself only in outline and from the outside, like a shorn chrysalis—even if she is immortalized by fame, as Achilles was. For Dante, hell is the place that preserves individuals as archetypes of themselves, formally eternal but empty of inwardness, the power to see their own present. So too Le Guin’s Dry Land, which becomes, like Eliot’s “Hollow Men,” an uncomfortable metaphor for the disillusioning effects of modernity. Dying is not absence but a feeble sort of self-caricature, and as Cob shows, it can happen even when you are alive. Cob is Le Guin’s villain only because he actively seeks a transformation that seems terrifyingly inevitable anyway.

*

So where is Rilke? I did promise him.

Rilke is the most obvious allusion in the sequence concluding The Farthest Shore, and the most hopeful. The Mountains of Pain are his. They come from Rilke’s tenth Duino elegy, where the speaker, a recently-dead youth travelling through the “Land of Pain,” enters its eternal mountains. Of these mountains, he is told by a Lament (the guardians of the Land of Pain):

… Our forefathers

worked the mines in those giant mountains; among humans

you’ll sometimes find a shard of primeval grief,

or a slag of petrified wrath from an ancient volcano.

Yes, those come from there. We used to be rich.

Accordingly, Arren, after carrying Ged out of death through the Mountains of Pain, finds one of these shards in his pocket:

It was a small stone, black, porous, hard… he felt the edges of it in his hand, rough and searing, and felt the weight of it, and knew it for what it was, a bit of rock from the Mountains of Pain… He held it in his hand, the unchanging thing, the stone of pain. He closed his hand on it and held it. And he smiled then, a smile both somber and joyous, knowing, for the first time in his life, alone, unpraised, and at the end of the world, victory.

“Alone, unpraised”: so Le Guin marks out Arren’s victory as his first authentic recognition of his own worth (and authenticity here bears its full existential weight, as it does in the rest of the Earthsea trilogy*). The Farthest Shore is Arren’s bildungsroman, and Arren’s self-knowledge coalesces around the hard reality of the pain he chose to endure. The choice is important for Le Guin, since she does not consider pain by itself a virtue. Should Arren have joined Ged’s quest purely for the sake of his own development, his pain would have meant little, since any other pain might have yielded the same result. But because Arren chose to endure pain as the necessary consequence of a greater purpose than his own, his pain is “the unchangeing thing”: its value is not fungible (“We used to be rich,” says the Lament). What Arren’s pain offers to him cannot be bought as Cob buys life. It is worth mentioning here that earlier in Rilke’s elegy, we learn that the Land of Pain exists “just beyond… the last of the billboards, plastered with signs for ‘Deathless,’ / that bitter beer which tastes sweet to those who drink it… just beyond those boards, just the other side: the real world.” Arren’s stone of pain signals that he has chosen the real world, real life and real death, over the innumerable billboards advertising salable false lives, whether they be fame or power or immortality.

“Choosing real life” is the Earthsea cycle’s favorite definition of maturity. However, it does not solve the narrative problem that whatever Arren has learned, when he dies some part of him will go to the Dry Land. But perhaps Le Guin’s point is that this hollow, eternal self was never the true self in the first place—Cob only thought it was, and this is his error. As Ged remarks to Cob of the world’s most famous mage, a man named Erreth-Akbe:

Did you not understand that he, even he, is but a shadow and a name?… He is there—there, not here! Here is nothing, dust and shadows. There, he is the earth and sunlight, the leaves of trees, the eagle’s flight. He is alive. And all who ever died, live; they are reborn and have no end, nor will there ever be an end.

At the end of Rilke’s elegy, the dead youth and his guide encounter the Font of Joy. The Font springs in the Land of Pain but flows backwards from death through life: “She names it / reverently and says:–‘Among the living / it becomes a powerful stream.’” If Ged’s speech and the Font mean the same thing—and I think they do—then their shared afterlife is no longer Homer’s or Dante’s or Eliot’s, but Ovid’s, an eternal, fructifying cycle. And life’s truth, its authenticity, is not the stability of its outward forms—names, individuals—but the energy with which it endlessly changes pain into joy, death into life, and back again. As Rilke writes at the end of the elegy:

But suppose the endlessly dead were to waken an image in us:

they might point to the catkins hanging

from the empty hazel trees, or direct us to the rain

spattering black earth in early Spring.

and we, who always think of happiness

rising, would feel the emotion

that almost confounds us

when a happy thing falls.

***

The translations I’ve used for this post:

Edward Snow’s The Poetry of Rilke (New York: North Point Press, 2009).

Jean and Robert Hollander’s The Inferno (New York: Random House, 2002).

*Supposedly, in the 1980s Le Guin repudiated the concept of “true names” and its association with authenticity. Given the recent swing in the academy, and culture more generally, back towards authenticity/earnestness/idealism as valid goals, I would be curious to hear what she thinks of it now. However, she is wise enough not to read criticism of her own fiction!