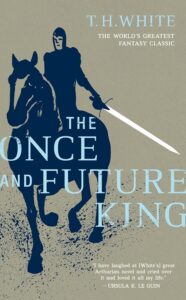

This year was terrible, but I was fortunate to read a lot of good books, including some old favorites (Le Guin’s Earthsea cycle, T. H. White’s The Once and Future King) and some very long novels (Byatt’s Babel Tower, Dostoevsky’s Brothers Karamazov, and Yanagihara’s A Little Life; I loved the first, liked the second, and was amused by the screaming egginess of the third). I also read a fair number of trans books, all good, several excellent. Trans writing is having a moment now. I’m grateful for it, though I don’t buy the lazy truism that oppression produces great art.

My favorites of the new or new-to-me books were A.S. Byatt’s Babel Tower (1996), Jeanne Thornton’s A/S/L (2025), Isaac Fellman’s Notes From a Regicide (2025), Angela Carter’s Wise Children (1991), and Ursula K. Le Guin’s Orsinian Tales (1976). All five are masterpieces; please read them if you haven’t. Compiling this list, I realized that all five are also ekphrastic novels centrally concerned with the question, “what good can art do?” Their answers vary, but none are uncomplicated, or naïve, or hopeless.

What can art do? I think about this question a lot. This year, art did not stop CECOT, ICE, genocide in Palestine, or the worldwide attacks on trans people. This year, art also kept me, and a lot of other people, going. I didn’t realize until sitting down to write this blog the extent to which reading was my lifeline through months when I felt catatonic with fear and grief. Is that enough? I don’t know. In the Terrance Hayes collection I’m reading now, the first poem warns, “In a second I’ll tell you how little / Writing rescues.” The epigraph to my academic book was a line from Auden’s Yeats elegy I think about daily: “For poetry makes nothing happen: it survives.”

Or Le Guin, from an Orsinian Tales story set in 1938:

“Music will not save us, Otto Egorin had said. Not you, or me, or her, the big golden-voiced woman who had no children and wanted none; not Lehman who sang the song; not Schubert who had written it and was a hundred years dead. What good is music? None, Gaye thought, and that is the point. To the world and its states and armies and factories and Leaders, music says, ‘You are irrelevant’; and, arrogant and gentle as a god, to the suffering man it says only, ‘Listen.’ For being saved is not the point. Music saves nothing. Merciful, uncaring, it denies and breaks down all the shelters, the houses men build for themselves, that they may see the sky.”

Anyway, here’s what helped me see the sky in 2025.

As always, books are listed in the order I read them, save for authors of whom I read more than one book; those I’ve grouped.

*

Anthony Powell, A Question of Upbringing; A Buyer’s Market (novels, 1951 and 1952). Billed as the English Proust, Powell isn’t.

Maylis de Kerangal, trans. Sam Taylor, The Heart (novel, 2014). Propulsive account of a heart transplant.

Hayao Miyazaki, Shuna’s Journey (comic, 1983). The sourdough starter of all Miyazaki’s greatest hits; who knew?

Emily Tesh, Some Desperate Glory (novel, 2023). Satisfying space opera that acknowledges but can’t overcome the problem that its genre demands stakes—the life and death of worlds—too big to ever hit home, emotionally.

A.S. Byatt, Babel Tower (novel, 1996). My favorite Byatt so far, a defense of artistic freedom that gives its counterarguments their full, disturbing weight, yet invites us to find in favor anyway. I read it alongside Some Desperate Glory and found its depiction of a rigged 1960s divorce trial more horrifying than the death of thousands of worlds.

A.S. Byatt, Still Life (novel, 1985). Byatt does Middlemarch, mostly successfully, though her discomfort with the omniscient commentator is palpable.

A.S. Byatt, Elementals (short stories, 1988). Simple, sensuous, and profound, like all good fairy tales.

Samuel Beckett, Waiting for Godot (play, 1952; reread). As bare and bleak as I remembered.

Tom Crewe, The New Life (2023). Exquisite prose.

Maya Deane, Wrath Goddess Sing (novel, 2022). Delightful. I came away wanting less Iliad and more rambling around Deane’s complexly multicultural Bronze Age Aegean and its syncretic universe of chilly, inhuman gods.

Jeanne Thornton, A/S/L (novel, 2025). A masterful, bittersweet celebration of the universes we co-create as teenagers, the worthwhile tragedies of trans friendship, and the trap of the “good person” as an ideal; also a sharp meditation on gaming and agency. Thornton is one of our best working writers of both character and ekphrasis. I can’t wait for her next novel.

Sofia Samatar, The Horizon, the Practice, and the Chain (novella, 2024; reread). A loving challenge to academics to follow our students and get free.

Torrey Peters, Stag Dance (novel, 2025). Peters does Cormac McCarthy (the title story, good) and herself (everything else, better).

Mary Shelley, Frankenstein (novel, the 1831 version, which I prefer; reread). Still rips.

Ada Palmer, Too Like the Lightning (novel, 2016). Wonderfully bizarre; dares to ask the question “what if a bunch of Enlightenment philosophes maintained world peace via a butterfly-effect set of assassinations?”—and answers, “it goes about as badly as the first Enlightenment did, and for largely the same reasons.”

Soula Emmanuel, Wild Geese (2023). Lyric in a way that occasionally strains its delicate, thoughtful character work.

Dennis Staples, Passing Through a Prairie Country (novel, 2025). A grimly funny casino ghost tale.

Georg Lukács, trans. John and Necke Mander, Realism in Our Time (criticism, 1964). Helped me recognize that my discomfort with a certain flavor of excessively-online left irony lies in its exuberant nihilism, which feels uncomfortably close to the fascist variety.

Natalia Theodoridou, Sour Cherry (novel, 2025; reread). A Bluebeard retelling of profound beauty and wisdom, Sour Cherry shows us how abuse traps people in stories that help them excuse it—but also survive.

Solomon J. Brager, Heavyweight (comic, 2025). Thoughtful graphic memoir of a Jewish transmasc navigating the networks of oppression, repression, and memory that surround their family’s Holocaust history.

Isaac Fellman, Notes From a Regicide (novel, 2025). A quiet, beautiful tribute to love as prosthetic, how we fill in one another’s lacks but also expand each other beyond the selves we thought possible (and how this model of care is something art articulates and state power grotesquely mirrors).

Christopher Chitty, Sexual Hegemony (criticism, 2020). Published in 2020 but written earlier, this dispatch from the 2010s makes a compelling, if scantily-historicized, argument that homosexuality is a function of shifts in capital accumulation and labor. The book can’t ever quite decide if it means homosexuality as visible social category or homosexuality as “acts of desire,” and the slippage between the two often feels torturous, as if Chitty, who finds psychoanalysis trite, is desperate to unearth, in the history of capital, an account of the self’s waywardness that his own Marxism disdains. It has huge lacunae around race and gender—it can’t imagine that capital would subvert its own interests to preserve white supremacy, and blames bourgeois ideology on “the feminization of the public sphere” without an attendant account of women’s place in the history of capitalism—but they’re excusable given the circumstances: this is a dissertation published posthumously by the writer’s friends after he committed suicide in 2015.

Hanya Yanagihara, A Little Life (novel, 2015). I was expecting the voyeuristic approach to abuse and self-harm. What I wasn’t expecting was the extent to which this novel is egg literature: a writer—normally I’d say “book,” but ALL feels overburdened with authorial intent—who desperately desires a particular type of masculinity, then ruthlessly punishes herself for wanting it. It’s visible from space.

Walter Benjamin, Reflections, trans. Harry Zohn (criticism, 1968). Brilliant, dense, mannered, and depressingly prophetic.

Grace Paley, Enormous Changes at the Last Minute (short stories, 1974). Wry little stories, each concealing a novel’s depth of humanity.

Vladimir Nabokov, Pale Fire (novel, 1962). A clever tour-de-force with occasional flashes of deep feeling; a moving elegy of real exile from a fake country; a tribute to the truths of literary artifice.

Angela Carter, Wise Children (novel, 1991). A virtuosic tragicomedy and larger-than-life love letter to theater in all its dirt, glitter, and excess; as much a masterpiece as Pale Fire, though genre and gender meant Carter never got Nabokov’s accolades, as she—and this book—understood all too well.

Vladislav Vančura, trans Carleton Bulkin. Marketa Lazarová (novel, 1967). Cynical, bizarre Modernist fable of human cruelty and desire in medieval Bohemia.

Syr Hayati Beker, What a Fish Looks Like (short stories, 2025). A huge-hearted, wildly inventive collection of interlinked stories about a group of queers falling in and out of love with the world and each other as they debate whether love is enough reason to stay.

Ryka Aoki, Light From Uncommon Stars (novel, 2021). Gentle science-fantasy about a brilliant trans violinist who gains (then sort-of loses) two high-powered space moms, and a celebration of the immigrant communities of the San Andreas valley.

Alexis Hall, Mortal Follies (novel, 2023). Genre romance isn’t my thing, but I’m still not sure this is a good example of the form—twee rather than witty, with paper-thin characters.

Sylvia Townsend Warner, Kingdoms of Elfin (short stories, 1977). Enchanting fairy stories with a hard crust of political realism.

Seamus Heaney, The Spirit-Level (poetry, 1996). What an ear.

Isabel Cañas, The Possession of Alba Díaz (novel, 2025; reread). My favorite of Cañas’s books yet, with a lot of delicious historical detail and a delightfully fanatic villain.

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, Wizard of the Crow (novel, 2006). Sprawling comic epic skewering the inanity of colonial capitalist corruption, with intricate plotting and a huge scope; a book whose mastery is so effortless it only strikes you on reflection, when you’ve finished and wonder how the trick was done.

Ursula K. Le Guin, A Wizard of Earthsea (novel, 1968; reread). On this reread, it struck me how much all three novels of the original Earthsea trilogy are, at heart, accounts of the love between teacher and student, and how that love can transform; from the student’s perspective in Wizard and Atuan, and from both student and teacher’s in Farthest Shore. No wonder I still love them.

Ursula K. Le Guin, The Tombs of Atuan (novel, 1970; reread). Probably the best of the original trilogy.

Ursula K. Le Guin, The Farthest Shore (novel, 1972; reread). Though this book ends with Arren being crowned, Le Guin’s disinterest in monarchy is already clear. The world isn’t saved by kings, but by the collective refusal of greed at the expense of life.

Ursula K. Le Guin, Tehanu (novel, 1990; reread). Le Guin discovers ‘80s feminism and manages to retain mostly its good bits.

Ursula K. Le Guin, The Other Wind (novel, 2001; reread). Earthsea is the only high fantasy series I know whose final two novels, written decades later, upend its entire magical metaphysics because its writer’s own metaphysics have matured. The Other Wind and Tehanu reflect Le Guin’s recognition that her naming-magic was an essentialism she no longer endorsed: the idea of a magical “true name” clings so fearfully to a stable identity that it’s ultimately indistinguishable from the greed she critiqued in The Farthest Shore. Instead of retconning or mea culping, she changed her world and freed her characters.

Ursula K. Le Guin, The Dispossessed (novel, 1974; reread). Every time I reread this novel I’m newly sad that Anarres doesn’t exist, and that I’m not brave enough to help build it here.

Ursula K. Le Guin, Lavinia (novel, 2008). It’s clear Le Guin loved Virgil, as a poet and as an imagined man, because she fashions him after her favorite archetype: Estraven/Ged/Shevek, the wise, quiet, practical teacher with a troubled conscience.

Ursula K. Le Guin, Orsinian Tales (short stories, 1976). I was too young for this collection the first time I read it; I hadn’t met enough people or thought hard enough about history. Now I think it’s some of Le Guin’s best work, her statement on what the twentieth century, especially the Cold War, meant to central Europe. Its closest peer is Jan Morris’s masterpiece Hav.

Fyodor Dostoevsky, The Brothers Karamazov (novel, 1880). Halfway through this novel I joked that Dostoevsky’s gleeful bathos refused his characters the nobility of tragedy, whereupon the book’s pummeling climax extended that nobility to everyone, somehow without losing its winking cynicism about humans’ ability to ever uphold the ideals they create. That we create them anyway, it maintains, is our grace.

Ursula Whitcher, North Continent Ribbon (short stories, 2025). Spare, interconnected stories about the growth of a resistance movement against tech-assisted slavery.

Hernán Diaz, In the Distance (novel, 2017). Avoids sentiment so strenuously that its bleakness bends right back around to sentiment’s cousin, the lurid; this inversion seems intentional, the kind of experiment only a good writer can pull off, even if it doesn’t always succeed.

Premee Mohamed, The Siege of Burning Grass (novel, 2024). A quiet, pointed, thoughtful exploration of nonviolence as a resistance strategy whose conclusions are somewhat undercut by shying away from giving the opposing position sufficient weight.

Orhan Pamuk, trans. Maureen Freely. Istanbul: Memories and the City (memoir, 2003). Melancholy tribute to a melancholy city, braided with a child’s history of growing up in the shadow of a collapsed empire trying, masochistically, to westernize.

Adrian Tchaikovsky, Elder Race (novella, 2021). Competent, unexciting.

Vivian Blaxell, Worthy of the Event (criticism, 2025). Bravura essay on human dignity that swaggers from Spinoza to shit.

George Orwell, Nineteen Eighty-Four (novel, 1949; reread). I approached this reread anticipating that Orwell’s totalitarian state would seem arid compared to our own clownish fascism, but instead the book remains horrifyingly prophetic.

Peter Kropotkin, Mutual Aid (criticism, 1902). Bracing and hopeful, especially in its reminder that written history overrepresents conflict because it finds conflict more interesting than quotidian communality.

Andrea Gibson, You Better Be Lightning (poetry, 2021). Big-hearted, though seems like it would be more powerful performed aloud.

Anton Solomonik, Realistic Fiction (short stories, 2025). The trans guys in this collection feel as if they’re being puppeteered from a thousand miles up; their subjectivity is painstakingly detailed and mostly uninhabited. It’s clearly intentional, an ironic portrait of alienation, dysphoria, and the vacuity of American masculinity. It’s often very funny. As I moved through the collection I was reminded of A Little Life: they share an authorial overdetermination, where an attitude allegedly restricted to character has seeped into the bones of the thing. In ALL it’s a tawdry desire for masculinity; here it’s an anxious contempt for that desire, perhaps for all desire.

Hannah Arendt, The Origins of Totalitarianism, “Totalitarianism” (criticism, 1951). Arendt’s account of how social isolation makes fertile ground for totalitarianism by luring lonely people into a fictional world—separate from reality and ruled by iron internal logics that inexorably discover ever-more extreme and dehumanizing conclusions—reads like a prophecy about the relationship between digital siloing and radicalization.

Various authors, what about the rapists? anarchist approaches to crime and justice (criticism, 2015). Grapples cogently with the limits of accountability processes, mostly around capacity.

Tamara K. Hareven and Randolph Langenbach, Amoskeag: Life and Work in an American Factory-City (history, 1978). Stark, vivid interviews from workers at what was at one time the largest textile mill in the world, and a testament to the stubbornness and fortitude of human community in the face of brutal labor conditions.

Giuseppe di Lampedusa, trans. Archibald Colquhuon. The Leopard (novel, 1958). A melancholy deceleration of a novel that broods on the collapse of Sicily’s aristocracy and the inevitable passage of time.

William Maxwell, So Long, See You Tomorrow (novel, 1979). Perfect miniature tragedy.

Margaret Killjoy, We Won’t Be Here Tomorrow (short stories, 2022). Fierce, wise.

Rudolf Rocker, Anarcho-Syndicalism: Theory and Practice (criticism, 1937). More history than I was looking for, though it let me brush up on Chartism.

Rachel Meredith, Girl Next Door (novel, 2025). An examination of betrayal and doxxing wrapped up in a playful rom-com about IRL fanfic; the genre’s requisite HEA became a fascinating gravity well that demanded, by book’s end, everyone more or less forgive each other, even if that forgiveness wasn’t earned.

Andrea Long Chu, Authority (criticism, 2025). I think Chu knows she’s our generation’s Sontag, so deferentially disclaims being so on the first page of this delightful collection, which is anchored by a miniature history of criticism that plants Kant at the root of liberal critics’ agonized catch-22—the freedom to think anything and obligation to endorse nothing.

Jane Austen, Northanger Abbey (novel, 1817). Fun if slight; but then, it’s juvenilia.

Virginia Woolf, The Waves (novel, 1931; reread). Woolf’s masterpiece.

Mirha-Soleil Ross, ed. Gendertrash from Hell (collection, 2025). We still have so much to learn from this trans zine, whose critiques are—depressingly—as sharp as they were in the ‘90s.

Chinelo Okparanta, Under the Udala Trees (novel, 2015). Sweet, hopeful coming-out story.

Yiyun Li, Things in Nature Merely Grow (memoir, 2025). Austere and unforgiving; Li rejects both flabby grief and her own fury at it.

Anne Carson, Men in the Off Hours (poetry, 2000; reread). As elliptic the Greeks she translates, and so most adroit when imagining wordier people: Woolf, Tolstoy, Akhmatova.

Willie Edward Taylor Carver Jr., Gay Poems for Red States (poetry, 2023). Earnest poems about growing up gay in Appalachia by a teacher who bravely testified before Congress about protecting queer people in secondary school—and lost his job for it.

Emily Austin, We Might Be Rats (novel, 2025). Breezy epistolary about smalltown suicide whose structural conceit, conceptually terrific, doesn’t quite pay off.

Hamid Ismailov, trans. Shelley Fairweather-Vega, We Computers (novel, 2025). Densely brilliant; my ignorance of Persian, Arabic, and Slavic poetic traditions meant I missed more than half of it. Written before LLMs, the book’s analyses of their effect on poetic reception are prescient, if a little naïve.

T. H. White, The Once and Future King (novel, 1958; reread). I remember loving this novel as a kid, and rereading it for the first time in decades, I see why: its core story, like Le Guin’s Dispossessed and Hugo’s Les Misérables, is about people trying to create a good society, failing, and persevering anyway because even a failed attempt is worth it.

Quiara Algería Hudes, The White Hot (novel, 2025). Courageous rage, if the prose is more fury than sound at points. I had trouble swallowing the sequence where the lead rediscovers her body living in a forest for a week, yet treats hunger as an optional, philosophical problem.

Emily St. James, Woodworking (novel, 2025). Plain and lovely and delightfully midwestern story of intergenerational trans friendship.

Saneh Sangsuk, trans. Mui Poopoksakul, The Understory (novel, 2003). Mesmerizing faux memoirs of a monk elegizing the deep Thai jungle where he grew up, a hostile otherworld ruled by tigers.

Moshtari Hilal, trans. Elisabeth Lauffer, Ugliness (criticism, 2023). Lucid if familiar overview of the relationship between western aesthetics and eugenics, though its critique of gender and bodily transformation conveniently ignores trans people.

Marilyn Hacker, Winter Numbers (poetry, 1994; reread). Elegant struggles to align different sizes of grief: Hacker’s breast cancer; her friends dying of AIDS; genocides old and new; the incomprehensibility of joy in terrible times.

*

That’s it for this year! See you in 2026, unless either something extraordinarily good happens in my publishing life or something extraordinarily bad happens in my real one.